Even though we look around us and see plastic everywhere, in every shape and imaginable application, metals are still a more commonly used raw material in machined products. Metals are the legacy material of choice due to their strength and relative ease of bonding. However, advances in polymers are making them useful alternatives for everything from car parts to sports equipment. But, higher costs and sometimes volatile substances released during the processing of polymers mean that metals are still the preferred choice of manufacturers for many applications.

Joining metals is the crux of creating assemblies from steel, aluminum, iron, or any alloys that need to be combined to form something greater than the sum of their parts.

The proverbial joint (or interface) between materials transfers the applied load from one component to the next. A long-proven method of joining metals so that the stress distribution is evenly distributed throughout the joint is to weld them.

Mechanical fasteners (bolts or rivets) are still frequently used, but they can add significant weight to a structure. All of the transferred stress is concentrated in the fasteners and the holes through which they pass. To resist fracture, the material must be made thicker and heavier to sustain these stress concentrations.

While welding is a great way to make a clean-looking joint rather than a fastener assembly, it is not without its challenges.

Rethink your adhesion manufacturing processes with Surface Intelligence.

The Art of Arc Welding

Welding techniques fall into two major categories, each with its own particular strengths and weaknesses.

Metal Inert Gas welding (or MIG welding) is the most common in manufacturing because it is considered a “semi-automatic” welding process and can incorporate robotics fairly easily. MIG welding works by continuously feeding a spool of metal wire through the torch which melts the wire and fuses it to the metal surface being joined. MIG is a more “point-and-shoot” approach than the more refined and precise manner of its cousin, Tungsten Inert Gas welding.

Tungsten Inert Gas welding (or TIG welding) requires a highly skilled technician to ensure high-quality work because it’s a two-handed operation that uses a pedal to send just the right amount of gas through the torch. It can be a slow and meticulous art form in its own right, not merely a means to an end. This isn’t the most practical joining method, but it can produce clean, aesthetically pleasing joints and ornamental flourishes if that’s what you’re after.

Regardless of the method employed by manufacturers, many aspects of welding need to be controlled to create a strong joint that meets performance expectations. The shield gas needs to have adequate coverage, the temperature and amperage need to be appropriate for the type of materials being welded, polarity needs to be dialed in, the filler metal needs to be applied properly, and so on.

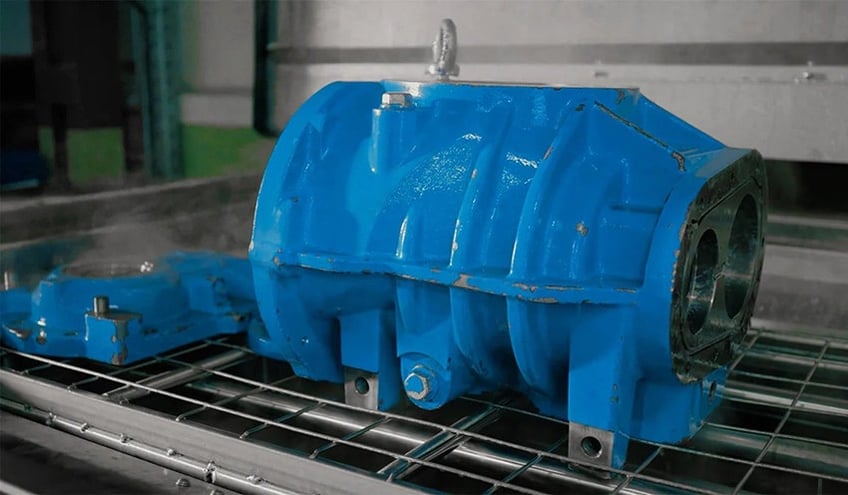

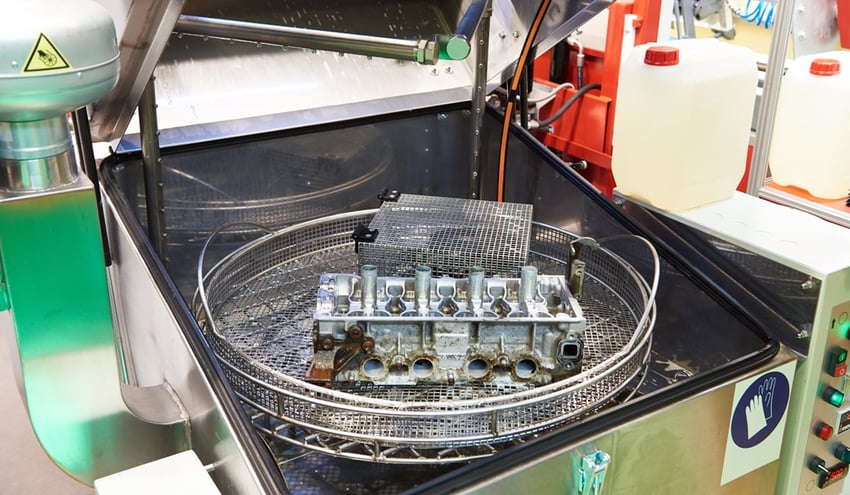

One concern that can often get bundled into other things you need to pay close attention to is the cleanliness of the base and filler materials. When contaminants such as oils, grease, and oxides are on the surface of the metals, it is nearly impossible to create a strong bond between the molten metal and the base metal.

Why Should You Clean Before Welding?

Two major failure modes occur when contaminants are left on the surface of metals being welded.

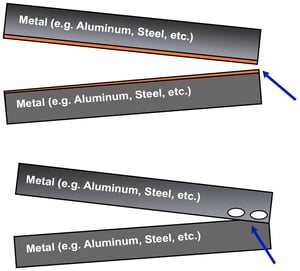

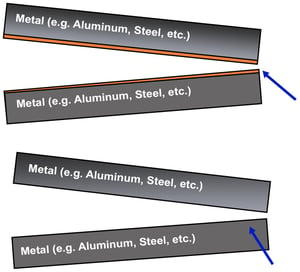

When contaminants like grease from the skin, oils from cutting procedures, or other films are heated by the flame of a welding torch, they can volatilize (boil) and prevent the molten metals from flowing properly. If the metal doesn’t flow fully or at a controlled rate, voids can be created within the welding bead.

When contaminants like grease from the skin, oils from cutting procedures, or other films are heated by the flame of a welding torch, they can volatilize (boil) and prevent the molten metals from flowing properly. If the metal doesn’t flow fully or at a controlled rate, voids can be created within the welding bead.

Voids are essentially little air bubbles trapped within the bead that amplify stress on the joint seams. This is called porosity and is usually caused by oxygen, nitrogen, and/or hydrogen getting trapped inside the weld. Hydrogen release is most often due to an improperly cleaned surface.

Primer coatings can also create undesirable fumes that may get caught in the weld and wreak havoc on the joint's strength.

Voids and porosity have various ways of showing up visually in the weld, but each is destructive.

Similarly, another destructive consequence of leaving contaminants on the metal surfaces is an incomplete weld. Some contaminants are neutralized by the heat of the welding torch, but if the contaminants require more heat to be removed than what is applied, the metal may not flow completely over the surface or will only fuse to a shallow depth. This creates a brittle and insufficient joint.

Similarly, another destructive consequence of leaving contaminants on the metal surfaces is an incomplete weld. Some contaminants are neutralized by the heat of the welding torch, but if the contaminants require more heat to be removed than what is applied, the metal may not flow completely over the surface or will only fuse to a shallow depth. This creates a brittle and insufficient joint.

The most common way of testing for both failure modes is to test after the welding has occurred, making the validation process expensive and destructive. Grinding out a weld and redoing the job is difficult, and the materials are already compromised, making it all the harder to create a strong joint on the second or third try. Radiography, ultrasonic inspections, and other non-destructive tests can detect voids or weak welds once the work has been done. Still, they are reactionary tests and don’t indicate what led to the deficient weld. It’s impossible to know if the surface was not clean enough or if another factor was not fully controlled with the torch and metals.

How to Predict a Strong Weld

Contact angle measurements are a useful method of testing the cleanliness of metals before attempting a weld. This method measures the behavior of a drop of liquid on a surface to gauge the surface energy of the material in question. Surface energy is essentially how chemically clean a surface is, and if the metal has high surface energy, the liquid drop will wet out on the surface. The liquid is sensitive to the same microscopic contaminants that the molten metal gets tripped up by. This is an excellent test for welding because the way the droplet flows on the surface clearly indicates how the metals will react to each other and whether their flow will be unimpeded.

Get hands-on with your surface cleanliness with the Surface Analyst 5001.

One of the greatest advantages of contact angle tests is that they are non-destructive and can be done directly on actual parts of the production line. The equipment used to take contact angle measurements can be automated, so it fits perfectly with any high-rate manufacturing process. Portable devices are also designed for field inspections when repairs to welded joints are necessary.

To ensure your welding, brazing, soldering, cleaning, or adhesion processes are optimized to create the most reliable products, download the eBook "Metrics That Matter: Quantifying Cleaning Efficacy for Manufacturing Performance."